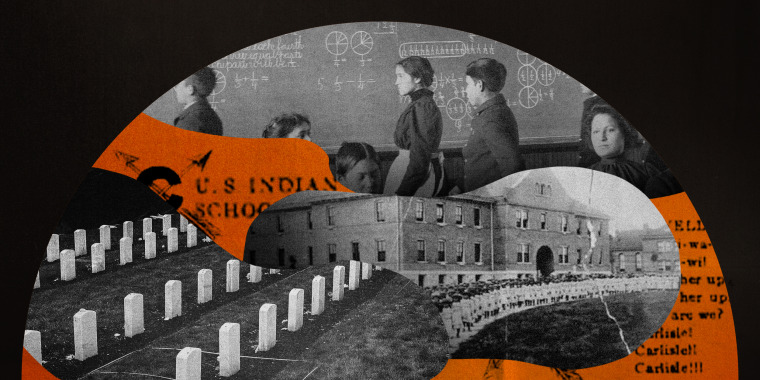

Over the four decades that the Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School operated in Michigan, thousands of Native American children from across the country were taken from their parents and sent there to be stripped of their languages and traditions.

The U.S. documented five deaths of Indigenous children at the school from its opening in 1893 to its closure in 1934. But when the land where the school once sat was returned to the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan in 2010 by the state, the tribe’s researchers uncovered a more extensive history of the federal government's violence: records confirming the deaths of 227 children while at Mount Pleasant. The search for their remains is still underway.

The effort to figure out what happened to those children illustrates the challenge the Department of the Interior faces in its recently announced investigation of the more than 350 Native American boarding schools that operated in the United States for more than a century.

“The hard part is investigating the land and understanding what that boarding school did,” said Shannon O'Loughlin, chief executive of the Association on American Indian Affairs, a nonprofit cultural group, and a citizen of the Choctaw Nation. Thousands of children “lived, worked and died” in these schools, “far away from their own homes,” O’Loughlin said. “And time has passed.”

Canada offers a grim preview of what the Interior Department’s investigation might find: In the last month, the mass graves of more than 1,500 children have been found on the grounds of seven former residential schools in Canada. The staggering number of stolen children found at just those few institutions hints at the magnitude of what is to come as more grounds are investigated and more tribes locate their lost.

In the U.S., the investigation announced last month by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and the first Indigenous person to lead a Cabinet agency, aims to determine the scope and impact of the country’s Indian Boarding School Policy. The investigation seeks to gather information on the decades of institutionalized, federally funded cultural assimilation that has led to a host of negative outcomes for survivors and their families, from mental health issues to the loss of entire communal generations.

Tribes are bracing for a reckoning that many see as long overdue.

“The truth needs to be heard from the perspective of those who were harmed,” said Christine McCleave, the CEO of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition and a citizen of the Turtle Mountain Ojibwe Nation. “There needs to be some element of justice or transformation when assessing the impacts and the harms and the damage that was done and how to restore things that were taken or broken.”

The endeavor acknowledges a truth Indigenous peoples across North America have known for generations: that the governments of Canada and the U.S. didn’t just take the culture of the Indigenous children that both countries attempted to assimilate through boarding schools. In countless cases, they also took these children’s lives, each one representing a stolen generation.

Indian boarding school survivors’ experiences — oral histories collected by nonprofits in recent decades — have documented rampant instances of sexual and physical abuse, psychological trauma and deaths of children in facilities run by churches and the federal government. In some instances, children died from sickness, according to government documents, but survivors allege that there were other deaths due to abuse and neglect that schools did not report.

Stories of children being beaten for speaking their language, having their heads shaved and being forced to use the Bible as a way to understand how their culture was “barbaric” have been passed down through generations of Indigenous families. In many cases, the abuse caused survivors to sever their ties with their Native culture and history altogether.

The schools were part of a broader push to erase Indigenous cultures, a step in the colonization of North America. The United Nations definition of genocide includes "forcibly transferring" the children of one group to another group.

But any national reckoning on the atrocities won’t happen easily. Researchers and tribal leaders say that not only did the government try for decades to cover its tracks, but shortcomings in federal law raise serious concerns about how tribal nations will repatriate the remains of their lost children.

Barely more than a third of the government records for Indian boarding schools that operated in the U.S. have been located, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, a nonprofit organization that advocates for a truth and reconciliation process for the survivors of Indian boarding schools. Many documents were intentionally destroyed, while others exist in university archives and other historical collections, making finding them labor-intensive, especially for tribes that lack the research staff.

The Interior’s investigation will seek to identify the children who did not return home from boarding schools and their tribal affiliations, giving tribal nations an opportunity to not only understand the impact on their communities, but to also begin the process of repatriation.

Even if the Interior’s investigation manages to find records for most of the missing children, federal law makes finding their remains and bringing them home another problem entirely.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, a federal law, was passed in 1990 to stop the theft of cultural artifacts and human remains from graves and burial and community sites. But the law was designed to regulate theft by universities, museums and collectors, not to address the government’s role in genocide, or the legal pathway to healing.

Not only does the law have no provisions for the protection of unmarked graves, like the ones being uncovered in Canada and the U.S. — it also has no mechanism to require private landowners (like the Roman Catholic Church, which still owns many of the former boarding school sites) to cooperate with tribes or federal authorities in the repatriation of remains.

“There has to be legislation that applies equally, regardless of who owns the property that those children are buried on,” said O'Loughlin, of the Association on American Indian Affairs. “I don’t care if the church owns it, or Walmart or the feds. It should all be treated the same.”

In the absence of a federal law governing Native American remains on state or privately owned land, state laws will govern the path forward. One of the major concerns, O’Loughlin said, is that many states do not have laws regulating the discovery of unmarked graves.

The U.S. government’s campaign to destroy the cultural identity of Indigenous children and indoctrinate them with Christian beliefs started in 1879 with the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania and lasted into the 1990s. Over these decades, the Indian Boarding School Policy established 367 schools across the U.S.

The Mormon Church found the policy particularly useful. The church used it and built off the federal government’s Indian Adoption Project in the 1950s and ʼ60s to culturally assimilate an estimated 50,000 Indigenous children from across several states and tribal nations, Matthew Garrett, a professor at Bakersfield College, told The Atlantic. The scale of destruction led to the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978, a federal law that gave tribal nations some legal power to stop the theft of their children.

Many former Indian boarding schools are now in the care of the tribal nations they once sought to decimate, lying in various states of repair. Some are museums, like the Phoenix Indian School Visitor Center in Arizona and the Chilocco Indian School in Oklahoma. Others are perhaps beyond repair, including the round, stone buildings gathering dust among sandy bluffs in the Navajo Nation and the crumbling brick monuments to past offenses under the watchful eye of the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan.

Today, the students of Mount Pleasant are remembered nearby at the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways, where researchers have documented the stories of survivors and the policy that tried to whitewash their identity. The task of finding the remains of the 227 children on the 320 acres Congress once allotted for the former school’s grounds, if that’s where they are, will take time. The state of Michigan only returned 8 acres of the land to the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe of Michigan, which has found parts of the old school but has not yet identified any remains.

Another 300 acres of the former school grounds went to the city of Mount Pleasant. City Manager Nancy Ridley said that the city hopes to eventually use the land for business and residential development but has paused those plans as the tribe determines where the search for remains should continue.

Advocates, researchers and tribal leaders see the Interior’s investigation as the beginning of a long process, one that, if done effectively, will take much longer than Haaland’s tenure as head of the Interior.

“This is just starting the conversation,” said Dante Desiderio, chief executive of the National Congress of American Indians.

Before she became secretary of the Interior, Haaland was a Democratic member of Congress from New Mexico and introduced the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policy Act, which would not only document the history of the program, but also look into ways the destructive assimilation era continues to inform the Bureau of Indian Education, which runs public schools on reservations.

The bill was referred to a House committee last year but was never heard. Staff members for Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., are working with the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition to update the legislation and carry it forward.

“What we’re hoping is that the report from the Interior says more time is needed, more investigation is needed, and then the commission is able to pick up where the Interior left off,” said McCleave, of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition.

McCleave’s work entails the long and arduous process of helping survivors and their descendants not only deal with the mental and physical traumas that remain, but also the generational loss of cultural identities.

“These are examples of how the policy actually worked,” she said, “to assimilate Native peoples to the point where they are disconnected now from their tribal nations, communities, that language and culture.”