In 1995, there were 361 homicides in Washington, D.C., and that death toll, more than double last year’s tragic tally of 166, represented a five-year low. The violence of the drug wars of the early ’90s ravaged The District, earning the city the nickname, the “Murder Capital” of America.

From 1988-96, the population of the District of Columbia decreased by 15 percent as the city endured the highest murder rate of its history: nine straight years averaging more than a homicide per day. The population of Washington has since rebounded to 1970s levels, and in 2012, murders dropped below 100 for the year for the first time since 1963.

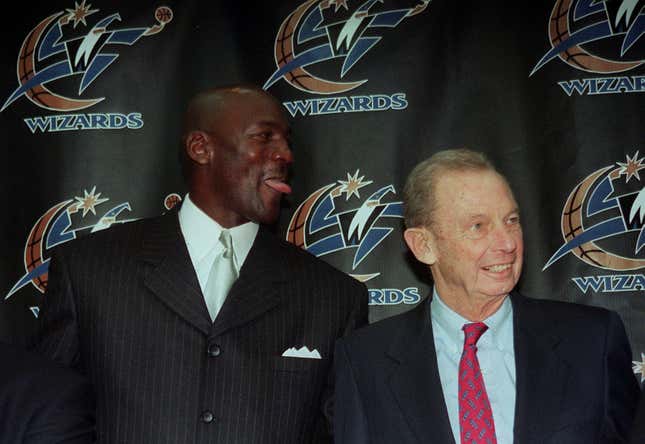

It was November of 1995, as D.C. approached its nadir, when Abe Pollin, the owner of the NBA’s Washington Bullets, announced that he would be changing the name of his team, which would soon be moving into the city from suburban Landover, Md. — the groundbreaking for what was then called the MCI Center took place a month earlier.

The District of Columbia had another nickname then, “Chocolate City,” as until the last decade, it was more than 60 percent Black as racial tensions swelled.

All of those factors: the violence, a race riot, and the new arena, are part of the popular lore of why the name change was made to the Wizards after a 900-number vote a few months later, but it was something else entirely that was the impetus for Pollin to abandon the Bullets name.

“My father had a very strong social conscience in general,” said the late Pollin’s son, University of Massachusetts economics professor Dr. Robert Pollin. “Not just around issues of violence, but in general. He was very active and very well known in the Washington, D.C. community for his involvement, philanthropy, and so forth. That’s just the way he was. So, for a wealthy businessman, he’s a very unusual person, in having such a strong social conscience.

“The issue was this specific thing of having this team named for something to do with gun violence.”

It wasn’t a pressing issue for Pollin, who bought the team in 1964, but according to his son, he thought about it more and more over the years, especially after moving to Washington.

“What put him over the edge: Yitzhak Rabin was a close friend of his,” Robert Pollin said. “I actually also knew Yitzhak Rabin and the whole family quite well. This was because Rabin had been the ambassador to the United States from Israel, before he went back and became prime minister. So, before he was a very well-known, world-renowned figure, they became friends because Rabin was living in Washington and my father was active in the Jewish community and supporting Israel. And they both liked to play tennis a lot. So, they knew each other very well. And they both shared a strong social conscience, in their own different ways. They were both prominent people in their own different ways. But they were both also very sincere people, I would even say humble people, in their own ways.”

Rabin was shot and killed on Nov. 4, 1995 after attending a rally in Tel Aviv, the gunman firing three shots.

“My father was absolutely devastated. He actually rented an airplane and took a hundred people from Washington to Rabin’s funeral in Israel. He was just beside himself. When he got back from the funeral, he said, ‘That’s it, I’m doing this.’ A lot of people told him not to do it, including Wes Unseld, who was the closest person to him in the world of sports. Wes felt committed to the name, because they won a championship under that name and Wes had been with the organization forever.

“People made fun of him, saying, ‘Oh, this is gonna change crime levels in Washington? You think that, Abe? How ridiculous.’ Of course he knew it wasn’t going to, but he said to me, ‘If it changes one person’s attitude, at all, and does less to glorify violence in our community, it will be worth it.’ So that was it.”

Unseld, the greatest player in Bullets history and the general manager of the team when it officially changed names, died earlier this month at the age of 74. His opinion mattered a lot to Pollin, who died in 2009, but the owner felt that changing the name was important enough to do it over Unseld’s objection. His mind was made up that it was the right thing to do.

Ultimately, that’s what it takes to get a team name changed: the owner’s conviction that it’s the right thing to do. In Pollin’s case, that meant for reasons of social conscience. For Washington’s NFL team, which Robert Pollin himself has called on to change its name, it probably will mean something else.

It isn’t like Daniel Snyder is unaware of the racism baked into the franchise he has owned since 1999, and it’s not like it’s impossible to get Snyder to bow to public pressure on racism issues. This month, Snyder’s team took the name of team founder and inveterate racist George Preston Marshall off a seating level at FedEx Field, a week after the removal of a memorial to Marshall at the team’s former home, RFK Stadium. But even as Nestle took candy off the shelves in Australia that bore the same racial slur of a name as the American football team, Snyder did nothing.

“Dan Snyder, his out in this is saying, you know, Abe Pollin made a personal, moral decision to change the name,” said Aviva Kempner, a Washingtonian documentary filmmaker whose work includes The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg and The Spy Behind Home Plate, about Moe Berg. “Dan Snyder comes in, and he’s just totally pig-headed about it. Personally, I’m very upset, because he’s also Jewish, and there’s something in our tradition that says it’s almost a religious teaching that we don’t insult people, that we try to be respectful. So, I’ve always felt, Dan, how can you be like this?”

Kempner is currently working on a film called Imagining The Indian, about Native American mascots and nicknames throughout sports, but particularly her hometown football team. She’s hoping to have it ready for next year’s Sundance Film Festival and is continuing to seek funding for the project, which includes Washington Post columnist Kevin Blackistone as a co-producer.

“I’ve only read his comments or heard his comments as to why he doesn’t want to do it,” Blackistone said of Snyder and the concept of a name change. “What could personally affect him in the way that Pollin was affected? … I’m not sure what could personally affect him, unless the other 31 owners in the league turn towards him and say you’ve got to make a change, or if the fanbase somehow said they wanted to make a change and showed that by not renewing season tickets, or if players of color in the league, who we in the media have made so many people believe have been politically agitized in the past few years, say they’re not going to play for a team like this anymore or play against a team like this anymore.

“That would be the only thing I could see that would convince him to do what Abe Pollin did with the nickname of Bullets.”

Players are starting to get some pressure not to suit up for a team with a racist name and logo, as Fawn Sharp, the president of the National Congress of American Indians, representing 500 tribal nations, said in a statement, “It’s time for the players to rip down that name like it was a statue of a Confederate general in their locker room.”

The tie to the Confederacy is apt, because Washington was the southernmost team in the NFL until the Dallas Cowboys entered the league in 1960. Marshall, trying to take advantage of this geography, held exhibition games in segregated North Carolina. And, for a time, the last line in the team’s fight song, now “Fight for old D.C.,” was actually “Fight for old Dixie.”

“I’m a multi-generation Washingtonian, and I grew up in a family that had season tickets to this team,” Blackstone said. “There was no bigger thing to have in Washington than season tickets to this team. The waiting list, it was legendary. There was no better stock to have. And people were connected to the team, the players, the colors, the fight song, which has a racist history, and I suppose the name. But I don’t think there is anywhere near a significant amount of this fanbase that would abandon this team if it changed the name, and there’s no evidence anywhere in the country for any team that’s ever changed a name, specifically from a nickname based on some beliefs about Native Americans. There’s zero evidence.

“People make adjustments, they move on, and they continue to cheer their team. Washington, D.C., is undergoing one of the fastest rates of gentrification in this country, anywhere, and I think the new populace is probably more concerned about embracing a team with this nickname than some of the people who they may be replacing.”

Except, they’re not even replacing them. The addition of teams throughout the South has eroded Washington’s appeal as a regional team, and the franchise’s ineptitude under Snyder hasn’t helped either. The waiting list no longer exists, and the games aren’t even sellouts. When Washington saw an uptick in attendance last year, it was because its games were an easy ticket to snag for visiting fans.

So, the heritage that Snyder is protecting is not only racist, it’s not even financially sound anymore. In Pollin’s case, the Bullets had been named for the Phoenix Shot Tower, a former ammunition foundry that is one of the historic landmarks of Baltimore, the first mid-Atlantic home of the franchise after moving in 1963 from Chicago, where they were known as the Zephyrs.

Knowing that Snyder lacks Pollin’s social conscience, it may well be a change of location that leads to a change of name for the football club, because after 23 years at their current stadium, Snyder is looking to upgrade.

“The city council said, whoever was going to buy the baseball team, they couldn’t be the Senators, because we don’t have ’em,” Kempner said. “And Eleanor (Holmes Norton, the non-voting delegate to Congress for the District of Columbia) says if [Snyder] thinks he’s gonna come in this city — and I’ll tell you, in this environment, he’s not going to be able to go to Maryland or Virginia, either, and in the end, it’s going to be pure economics. It’s either going to be protests, or the fact that he can’t build a new stadium. … Economically, he’s going to make a shitload of money, because he’ll sell all new shirts. It’s either the old memorabilia, or the new ones. He’s gonna make double the money, that’s what’s so stupid.”