In 2008 Dash Snow was interviewed by the French magazine Purple Fashion. He described his art as a kind of storytelling and said it was about "trying to preserve a moment". By way of illustration, he talked about a piece he had recently made entitled A Means to an End. With hindsight, his description seems chillingly prescient.

"Sometimes the story is more important than the visuals, like A Means to an End, the table with all the stuff on it, the empty bags of coke and dope, and needles and diamond rings and all kinds of stuff. I was living on Avenue C in this really screwed-up house. When I moved it took seven days to clean it up, and this is all the stuff we found."

On 24 July Snow was found dead in a room at the Lafayette House hotel in New York's East Village. At the scene, detectives found two empty cans of beer, an empty bottle of rum, 13 glassine bags bearing traces of heroin and three used syringes. A means to an end.

Snow's body was discovered by his girlfriend, the model Jade Berreau, and a friend of the couple, the photographer Hanna Liden. They had gathered for lunch in a nearby restaurant with some friends, apparently to discuss what to do about Snow's worsening addiction. The pair had rushed around to the hotel after Berreau had received a call from Snow in which he'd sounded distressed and incoherent. His last words to her were: "Goodbye. I love you. I'll see you in another world."

Snow was pronounced dead by paramedics at 12.24am. He was just 10 days away from his 28th birthday. If his life and art constantly blurred into one, his death, too, had been foreshadowed in his work.

"If you look at the books he made, one is called In the Event of My Disappearance," says his gallerist, Javier Peres. "It was as if he was disclosing his state of mind. I never encountered anyone who lived more wildly and recklessly and freely, but I think he had lived the life he wanted to live and he was done living it. He had done what he wanted to do."

Snow's friend, the photographer Ryan McGinley, who documented their shared downtown scene - the all-night parties, the drugs, the sexual adventurism - until it grew too dark for him, says ruefully that Snow's death was not altogether unexpected. "I guess I wasn't surprised. It was one of those phone calls you always expected but hoped might never come. But it was still mind-blowing. Dash had such energy, such life force."

In death Snow, whom the New York Times dubbed "The latest incarnation of that timeless New York species, the downtown Baudelaire", has become an even more iconic figure. In downtown Manhattan, his playground as a graffiti artist, tributes to him have already appeared on walls and buildings, some depicting his raggle-taggle image, others his graffiti tag, SACE. Last month that same tag was writ large across the facade of Deitch Projects on Grand Street in Soho, one of the hippest galleries in New York. At the gallery's request, the building had been "bombed" by a graffiti artist known as GLACER, one of Snow's close friends from his years running wild with a spray can as part of the IRAK graffiti crew. In the early hours of the morning, GLACER had sprayed a jet of paint on to the facade from across the street using a customised fire extinguisher.

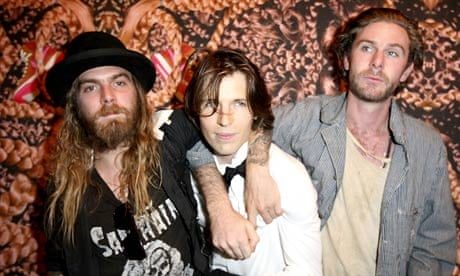

Inside, Snow's work - his edgy self-reportage Polaroids, collages, ornate homemade fanzines and grainy videos - was on display alongside the work of fellow New York artists-cum-friends. One wall was covered in McGinley's photographs of Snow and his crew drinking, smoking weed, snorting coke and having sex. Another featured an array of Snow's own Polaroids, the cruel and tender snapshots of a life lived - depending on where you are coming from - in the pursuit of total freedom or utter irresponsibility.

An adjoining room was filled with impromptu tributes from friends and strangers alike: collages, photographs, prose and poems, including one from the filmmaker and fellow free spirit Harmony Korine. All were a testament to Snow's charisma as well as his burgeoning cult status.

It was clear that Snow, through his wild life as much as the makeshift art he made from it, was viewed by both the coterie of cool young New Yorkers that knew him and the young wannabees who only knew of him, as a contemporary urban outlaw, a renegade, a self-styled outsider. At a cultural moment when those terms have all but lost their currency, Snow insisted on their continued importance, drawing on an "outsider" lineage that harked back to punk, the Beats, and beyond.

Snow's friend Kathy Grayson, a curator at Deitch who organised the memorial show, elaborates: "There are very few wild spirits in New York any more. Everyone plays it safe and goes for the money. But the more shitty and shallow New York gets, the tougher the rebellious people get. The whole street-based counterculture may have shrunk, but it's more diehard, and Dash was a figurehead for that kind of rebellion. He had that spirit of no fear that comes from being on your own and living by your wits. He hated authority, the police, anyone telling him what to do. He just danced to the beat of his own drum."

In Snow the New York art scene had finally found an edgy young artist to compare with Jean-Michel Basquiat. Like Snow, Basquiat had emerged out of graffiti subculture and died at 27 from a drug overdose. Unlike Basquiat's art, Snow's art had not yet been commodified by that same voracious art world, though whether this was down to his refusal to play the game or the perceived notion that his work was not original enough is a question that has been left hanging in the air by his untimely death.

Despite, or maybe because of, his self-styled mythology, and the confrontational and often wilfully adolescent thrust of his work - he once made a series of collages by ejaculating on to tabloid images of Saddam Hussein, then encrusting the sperm with glitter - Snow leaves behind an already fiercely contested artistic legacy. Even a casual perusal of the blogosphere reveals how much he divides opinion. He is dismissed as a chancer by some, exalted as a figurehead by others. Much of the scorn seems to come from those who saw Snow, as one blogger puts it, as "a rich kid and a hyped-up scenester". Both Grayson and Peres insist he was neither.

"People say he was a child of privilege," says Peres, who knew Snow for several years before he represented him, "but he rejected his family and their wealth apart from the support he had from his grandmother, who was a kind of patron."

Even before he became an artist, Snow's life was colourful, intriguing and seemingly intensely troubled. He was born into the kind of vast wealth that is usually described as "old money". In a 2007 New York magazine profile that incensed Snow and his friends, Ariel Levy wrote: "Snow's maternal grandmother is a de Menil, which is to say art-world royalty, the closest thing to the Medicis in the United States. His mother made headlines a few years ago for charging what was then the highest rent ever asked on a house in the Hamptons: $750,000 a season. And his brother, Maxwell Snow, is a budding member of New York society who has dated Mary-Kate Olsen."

Born to Christopher Snow and Taya Thurman - his aunt is the actress Uma Thurman - on 27 July 1981, Dashiell Snow was the great-grandson of Dominique and John de Menil, French aristocrats who amassed what is generally regarded as America's finest collection of art. It is based in a museum bearing the family name in Houston, Texas and includes works by Magritte, Ernst, Duchamp, Matisse and Picasso as well as American masters such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning. Their Rothko collection is kept in Houston's famous Rothko Chapel, itself a work of art.

"Dash grew up around Rauschenbergs and Twomblys," says Peres, "and he definitely had a sensibility that he had honed as his own, but without any formal training. He was someone who was giving voice to people who were on the outside, on the margins."

Snow's rebellion against his family, and his mother in particular, seems to have begun in earnest when, as a disruptive child, he was sent by her to a boarding school called Hidden Lake Academy in Georgia which specialised in the treatment of children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder. It was recently described by a local fundamentalist clergyman as "a last-chance boarding academy that offers objectively defined teenagers an alternative to prison". Whatever happened to Snow during his enforced tenure there, he held it against his mother until his death.

"He hated his mother more than anything," says McGinley. "But he never really spelt out why. He would even tell people his mother was dead. He never mellowed out on that.

I did meet his father once, and he was cool, a musician with a more bohemian spirit that Dash chimed with. I guess his closest family relationship was with his grandmother, Christophe. She kind of supported him and he loved her. She was a big part of his life."

When Snow was 18 he married a Corsican-born artist, Agathe Aparru, five years his senior. They lived with his grandmother for four years. It was Christophe who provided him with money when he was living by his wits on the streets of New York as a young teenager after coming out of Hidden Lake and fleeing forever the family home, and she who funded him as a struggling artist.

"His grandmother's help and support was considerable," says Peres, "but I think the amounts of money have been exaggerated considerably. Put it this way, I'm used to working with struggling artists before they make it, and I was shocked when Dash told me how much he was living on. It was small. Then again, he was a guy who didn't need much. He grew up in a world where he could not reconcile his wealth with what he was feeling. I think he rejected it in order to find some kind of freedom beyond it."

Initially that freedom manifested itself in petty crime and the buzz that being a graffiti artist constantly dodging the law brought. One unforgettable, and to a great degree, defining image of the young Snow in excelsis is McGinley's photograph of him balanced fearlessly and precariously on the ledge of a New York hotel roof, spray can in hand. His art, too, tended towards the transgressive and often the wilfully destructive. Alongside his friend Dan Colen, Snow created a series of installations called "hamsters' nests" that adhered to a ritual wherein they got off their heads on liquor and drugs, then shredded hundreds of books and whatever else came to hand. The nests were supposedly a male-bonding ritual and were created in hotel rooms - they famously trashed a suite in the Mayfair Hotel while staying there as guests of the Saatchi Gallery - as well as galleries.

"The one and only show they did at Deitch was a nest," says Grayson, smiling ruefully at the memory. "This crazy expression of bonding and freedom that got so out of hand.

It was absolute madness, sustained for over four nights, with different people dropping in and out, graffiti kids, street people, artists, all helping to essentially destroy the place. There's a photograph of Dash igniting a jet of vapour from a spray can amid all this paper and stuff while a skateboarder jumps over it. When my boss saw that, I almost lost my job."

Grayson tells another wild tale of Snow inviting a local homeless character, who goes by the name of Pap Smurf, to live in the gallery while the show was on. "Dash just had this ability to connect with every kind of person on the street. I watched him a million times walk up to truly terrifying-looking people and ask them if he could photograph their gang tattoos or their missing teeth. He had no fear and no sense of his own safety."

The artist Jack Walls, partner of the late Robert Mapplethorpe and someone whom McGinley describes as " a kind of mentor to us all", remembers the first time he met Snow. "He must have been 15 or 16, and he was friendly with Patti Smith's son Jackson because as children they had attended the Little Red School House together, which is where all the artists' kids go. I was walking along with Jackson and I saw this gang of graffiti and skate kids across the street. Suddenly one of them came running over and just stood right in front of us, blocking our way. That was Dash. He was kind of in-your-face even then, a little rebel."

Grayson, too, attests to Snow's "ability to be friendly and open and mischievous to everyone", then adds, laughing: "Except the cops." Snow's loathing of authority is the stuff of legend among the kids he ran with. It crops up again and again in conversation often as the defining element of his all-important street cred, his authenticity. Like the addiction that laid him low, though, it seems also to have been a symptom of something deeper and darker.

"He hated any kind of authority so much," elaborates Grayson. "Not just the cops, but anyone telling him what to do. So much so that it was hard to talk to him sometimes about certain things, or even advise him. Basically, if you didn't accept him for who he was, the way he was, he would not accept you. You could never tell him what to do, you had to just..." Her eyes fill up with tears and she shakes her head:

"Just appreciate him, I guess."

For a while, Snow seemed to have found a degree of contentment with Jade Berreau and their young daughter, Secret, but the demons that helped propel his art once again began to stalk him. In March of this year he checked into a rehab facility for the second time in a year. "He could go a month clean," his ex-wife Agathe told the New York Times, "but then if he had one glass of wine, it would become a bottle, then coke, then heroin. There was not a slow build-up; it was like a beast building up."

Ryan McGinley spent the Memorial Day weekend in late May at Jack Walls's house in upstate New York. Snow was there also but the two did not actually meet. "Dash never came out of his room the whole weekend," says McGinley.

"I didn't see him. He had gone to rehab just before that, but he had started using again. He was probably high in his room. I spent the day with Secret. It was kind of sad that I didn't see him. But it was a really great day, too."

Looking now at Snow's work, and his Polaroids in particular, you get a glimpse of a certain kind of early 21st-century urban American youth cultural sensibility: a sensibility that has its roots in punk and notions of outsiderdom and authenticity, and that, like punk, trails a recklessness bordering on nihilism as a kind of defining badge of identity. That sensibility is detectable in disparate places - in the early work of Harmony Korine, in the extreme outer reaches of rap and indie-rock culture, in some of the more reportage-based photographs of McGinley, and to a degree in the messy, always unfinished-sounding music, of Pete Doherty. You can trace it back through the work of photographers such as Larry Clark and Nan Goldin, mythmakers whose myths depend on an unvarnished and often hardcore portrayal of the lives of the beautiful losers they ran with, took drugs with and whose defiance and despair - and sometimes even their deaths - they turned into art of the most relentlessly uncompromising kind.

Snow was in, and of, that lineage, just as he belonged to that arty, druggy, downtown demi-monde that has survived even the gentrification of the entire Lower East Side. His art was not so much a reflection as an extension of it. He undoubtedly had an eye for the telling detail, the captured moment, and because of this, I think, his often unflinchingly confessional Polaroids will live on. They possess a grim beauty that those of us who do not live such wild and reckless lives seem to find irresistible.

"He wasn't a flash in the pan," says Walls. "He was up there with any of them. He had it. Completely. He was the whole ball of wax. He was for real."

Grayson concurs. "Was he a great artist? Hell yeah. He has the most impressive photo archive of any young American artist in decades, though most of it is unseen. There are boxes and boxes of Polaroids that just took my breath away. It's an extraordinary documentation of an extraordinary life. He had what all great photographers have: a signature. I just hope," she adds, again fighting back the tears, "that his work will come out in a considered way and that everyone will eventually see the legacy. There certainly won't be anyone like him again, that's for sure."