Nearly a decade in the making, the groundbreaking San Diego Museum of Art exhibition will showcase more than 120 works by the two artists

On the surface, the work of Georgia O’Keeffe and Henry Moore wouldn’t appear to have much in common.

Of course, there are the most obvious distinctions: one is a renowned American artist best known for her vibrant paintings of flowers and New Mexican landscapes; the other is a beloved British sculptor whose monumental, semi-abstract pieces are peppered throughout the United Kingdom.

For the record:

1:49 p.m. May 8, 2023This story has been updated to reflect the fact that the “O’Keeffe and Moore” exhibition requires an additional $10 fee for non-members of the museum.

This is, naturally, a very tidy summarization of two masters of the modernist art movement of the 20th century, and yet it’s not an exaggeration to state that each has become an icon in their own respective ways even if their work is seemingly dissimilar.

Almost a decade ago, however, Anita Feldman began to notice something curious. Around 2015, just a year after joining the staff of the San Diego Museum of Art (SDMA), Feldman went to visit the O’Keeffe studios in Santa Fe, N.M. This was followed by the staff of the O’Keeffe Museum visiting the Henry Moore Foundation in Hertfordshire, England, where Feldman had previously worked for 18 years. Within these meetings, Feldman says she began to see “connections,” an almost eerily “similar vision” shared by the two artists, despite them being a world apart both artistically and geographically.

“When I was looking at some of the O’Keeffe collections, it was almost like I was looking at it through Henry Moore’s eyes,” says Feldman, who serves as SDMA’s deputy director of Curatorial Affairs and Education.

“O’Keeffe was famous for taking pieces of animal bones and holding them up to the sky, looking through the holes and seeing the sky behind them,” Feldman continues. “Well, Moore did the same exact thing. That alone is such an amazing coincidence. That they had the same method of looking at things.”

“O’Keeffe and Moore” is the result of these connections and commonalities. Nearly a decade in the making, postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and finally opening Saturday, the groundbreaking SDMA exhibition will showcasemore than 120 works by the two artists. The exhibition will run through Aug. 27 before traveling to the Albuquerque Museum in New Mexico and then the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in Canada.

To call “O’Keeffe and Moore” ambitious is underselling it a bit. Spread out over five galleries, the exhibition has pieces on loan from 30 other museums, institutions and lenders. The exhibition is grouped into several categorical themes, each devoted to a particular element that inspired both artists. These include “Bones, Stones, Landscapes of Form” and “Seashells, Flowers, and Internal/External Forms,” among others.

“They’re both walking around the landscape where they lived, finding things and creating things from them,” says Feldman, walking one of the galleries, careful to point out works such as O’Keeffe’s “Ram’s Head, Blue Morning Glory” and one of Moore’s “Reclining Figure” pieces, both strikingly similar in the ways bones informed and influenced the works, figuratively and literally. Feldman later points to O’Keeffe’s enormous “Spring” painting as another example, with an antler and a vertebra contrasted with a mountain peak and white desert primroses.

“It was the largest painting she’d done up until this point. She painted it in 1948, only a couple years after Stieglitz died,” says Feldman, referring to O’Keeffe’s husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz. “It’s got the primroses which are symbolic of spring and renewal, as well as all her other favorite motifs. It’s kind of optimistic, and it’s like she’s ready to start over.”

For both artists, and especially O’Keeffe, objects such as bones, seashells and stones didn’t so much work as a metaphor for mortality, but as symbols of resilience and permanence — things that, much like the art itself, can last forever.

“I think that’s one of the more important concepts — that these objects don’t necessarily mean what we project them to mean,” Feldman says. “It’s about the form of, the shapes and the cavities. And then you have Moore, where it’s a figure that’s actually a composite of bones and stones.”

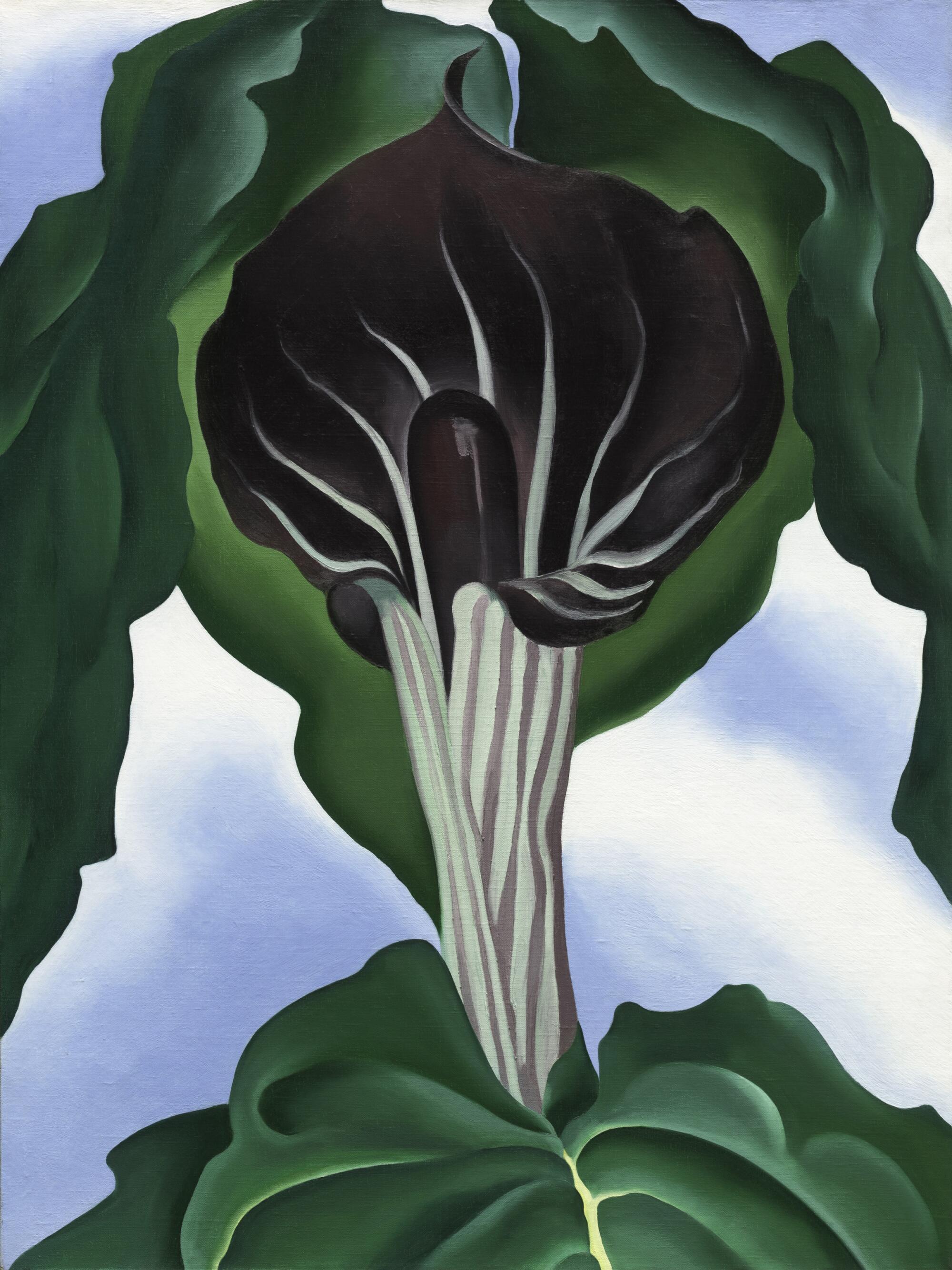

This logic extends and is perhaps most clearly represented in the gallery devoted to “Seashells, Flowers, and Internal/External Forms.” Here, the viewer can clearly see the ways in which both artists worked with objects they found in nature to produce works that took on humanistic qualities, both “representative and abstract,” as Feldman puts it. Of course, there’s O’Keeffe’s paintings of flowers, iconic not only due to her ability to render the flower down to its minimalistic, essential beauty (“Birch and Pine Tree No. 1” and “White Iris” are essential standouts in the SDMA exhibition), but also in how many viewers viewed them as aesthetically similar to a certain part of the female anatomy, an analogy she always denied.

“How can you look at O’Keeffe and say that she was just painting flowers? Or that she’s just painting women’s sexuality?” asks Feldman. “When you see that she’s really focusing on form in a very sculptural way, it’s the same language that Henry Moore was working in.”

Perhaps the most ambitious installation within the exhibition comes in the middle. Within the largest of the galleries, Feldman and SDMA have recreated O’Keeffe and Moore’s artist studios, complete with original artifacts, supplies, various ephemera and, in the case of O’Keeffe, some of her handmade pastels. The installation also includes painted views, rendered so as to resemble the landscapes the artist’s saw from the windows of their studio.

“There have been showcases of items from their studios before, but there’s never been complete recreations of either studios,” says Feldman. “What I really wanted to show is that they’re obviously very different artists, but there were so many similarities as well.”

Working closely in collaboration with the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, N.M., and the Henry Moore Foundation in Hertfordshire, England, the studio installations give the viewer a distinct sense of the ways in which the artists both collected and kept found objects, which would later influence their work and practice. Feldman says it will provide patrons “a real feeling of intimacy” with the artists, and, what’s more, it solidifies perhaps the most important shared commonality between O’Keeffe and Moore: That their art was, above all and throughout their careers, influenced and guided by the natural world.

“For me, coming at it as a Henry Moore scholar and seeing O’Keeffe’s studios, I knew about her work obviously, but I didn’t know how extensively she collected all these things, like bones and seashells,” Feldman says. “It was the same type of thing that Moore did. And there are lots of artists that picked up from nature, but both Moore and O’Keeffe had these vast collections that they accumulated over their entire careers. That’s where they got their inspiration and what was behind all their masterpieces. That’s what I wanted to show with this exhibition.”

As patrons exit the galleries through a workshop area for younger patrons to construct their own art using found objects, there are two quotes from O’Keeffe and Moore just above the work stations: “I would like my work to be thought of as a celebration of life and nature” from Moore and “My painting is what I have to give back to the world for what the world gives to me.” They are apt messages to depart with — converging sentiments from two masters that harnessed the natural world into timeless works of art.

“The main takeaways here are that both O’Keeffe and Moore, although they weren’t working together, weren’t close friends or anything, I wanted nature to be the thing that drew everything together,” says Feldman, adding that there’s only one documented occurrence of the two artists ever meeting. “That’s what I wanted to get across, this connection between forms and how they can be intimate.”

San Diego Museum of Art presents ‘O’Keeffe and Moore’

When: May 13 through Aug. 27. 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday-Saturday (closed Wednesdays), noon to 5 p.m. Sunday

Where: San Diego Museum of Art, 1450 El Prado, Balboa Park

Phone: (619) 232-7931

Admission: Free-$20 for admission. ‘O’Keeffe and Moore’ special exhibit admission is $10 extra for non-members

Online: sdmart.org

Combs is a freelance writer.

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.