The outrageous street-style tribes of Harajuku

Shoichi Aoki

Shoichi AokiThe wild, cartoonish street styles born in the Harajuku district in Tokyo marked a revolution in Japanese style. Lindsay Baker finds out if this spirit has been tamed.

“The fresh, colourful harvest of Japanese fashion,” is how pioneering photographer Shoichi Aoki describes his subject – the wild and quirky street style of Tokyo.

Shoichi Aoki

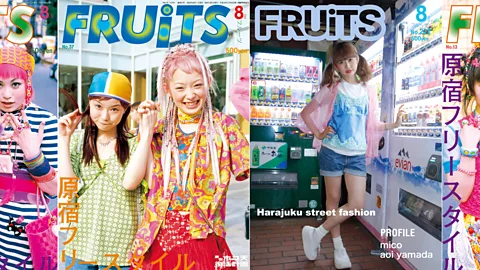

Shoichi AokiThe city has long been known for its expressive and cartoonish styles, and its Harajuku district as the gathering place for the most flamboyant and eclectic youth tribes of all. This cradle of sartorial eccentricity, full of fabulously inventive teen subgroups, boomed in the 1990s. And it was immortalised in monthly print magazine FRUiTS, a bible of innovative, outrageous personal style, created and published by the much-revered Aoki.

The magazine was ground-breaking and hugely influential, in both fashion and photography. Japanese teen tribes in all their style-conscious variety and dizzying complexity could be found in the pages of FRUiTS. From the girly Dolly Kei and Lolita to Gyaru, Decora and Ura-Hara, along with proponents of all things kawaii (cute), each tribe came with its own highly specific and inventive dress codes, concepts and rituals.

“Fashion is an act of self-expression, linked to the foundation of humanity,” Aoki tells BBC Designed through a translator. “It is as important as art, music and literature. And when I say ‘fashion’ I don’t mean ‘fashion business’.”

Interest in Aoki’s work has exploded in recent years, and a book was recently published of his images from the streets of London. His 1980s magazine, STREET, focused on Paris and London fashion “which were the most creative and interesting,” he says. “At the time, magazines were at the forefront of media, and it was media that I could publish myself... the internet did not exist.”

“At that time in Japan, the street fashion was not interesting to me,” adds Aoki. “Ten years later, in 1996, the new fashion in Harajuku was born. I believed that was the fashion revolution in Japan, and I decided to make FRUiTS.”

Shoichi Aoki

Shoichi AokiAs the UK’s ID magazine had done in the 1980s, Aoki and his team captured the looks of individuals while also showcasing the wider groups and networks to which they belonged, all before social media or hashtags even existed. “Most acts of expression have a system of being recorded and preserved, but there was no such system for street fashion,” he says. “I decided to make it my project to record street style.”

No more cool kids

But earlier this year Aoki made the decision to close the print edition of FRUiTS, saying at the time: “There are no more cool kids left to photograph.” This year, the magazine has been celebrating its legacy in association with retailer Opening Ceremony, with an installation at the brand’s New York store, alongside a release of merchandise and archive FRUiTS editions.

So why did the Harajuku district cease to be an epicentre of street style? And what does that mean for the state of Japanese youth culture? Has Japan’s fashion identity gone from cool to bland, wild to tame, edgy to mass market? To understand that, it’s important to understand how Harajuku’s street style phenomenon came about.

The district’s distinctive creative buzz was largely due to Hokoten says Aoki, referring to a shortened version of the Japanese phrase Hokousha Tengoku which means ‘pedestrian paradise’. The term describes a district of streets that are closed to traffic so that pedestrians can enjoy mingling. Harajuku was the most famous Hokoten in Tokyo, and its young people were bravely unorthodox in a traditionally conformist society, although each group undoubtedly conformed to its own codes.

Shoichi Aoki

Shoichi AokiIt seems that when the decision was made to allow traffic into Harajuku, it was the beginning of the end for its street-style mecca status. Harajuku as a gathering place ceased to be, and opportunities for its young and style-conscious inhabitants to mingle, impress and compare dwindled. By extension, this was also the beginning of the end for FRUiTS.

“It’s necessary to have a real space… Hokoten played an important role in maturing Harajuku fashion, and the fact that Hokoten disappeared was a big negative influence on it,” says Aoki. “The biggest reason I closed FRUiTS was that fashionable kids decreased in Harajuku. I couldn’t take enough photographs to publish monthly.”

“The significance of paper magazines changed too, and social media became more important than the position of fashion as self-expression or relationships with friends.”

The proliferation of corporate high-street retailers in the area also contributed to the demise of Harajuku’s cutting-edge style credentials: “Cheap clothing robs the existing space for young designers,” says Aoki. Added to this has been the entrance of Japanese street fashion into mainstream pop culture (look no further than Gwen Stefani’s music video for Harajuku Girls).

Alamy

AlamyAs far as Aoki is concerned, street fashion ceases to be ‘street’ when it enters the mass media: “I think truly interesting street fashion would not enter the mass media; by that time street fashion should have moved on to the next thing.”

Making statements

Exciting though the scene was, in Aoki’s view, there was no message of rebellion or even any value system in the flamboyant dress codes: “Nothing, just a fun expression. I like that.”

Yuniya Kawamura sees it differently. “The phenomenon is an ideological one,” she writes in her book Fashioning Japanese Subcultures. A Professor of Sociology at the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York, Kawamura is also the author of the best-selling Fashion-ology and the recent Sneakers: Fashion, Gender and Subculture, and sees the street-style scene as more than just a bit of fun. She tells BBC Culture: “It’s not just about a group of youngsters in distinct clothes. Their stylistic expression is a reflection of their values, norms, beliefs. The emergence of a subculture means that there is a community trying to send a social message to the public. Sometimes, the members themselves are not even aware of it.”

She points to the Gyaru group, from Tokyo’s Shibuya district, which is typically characterized by heavily bleached or dyed hair, highly decorated nails, and dramatic makeup. “The Gyaru phenomenon started in the mid-1990s as Japan went into deep recession... They tanned skin artificially to look tough and dressed in bright sexy clothes. Their basic life philosophy is: engage in rowdy behaviour such as drinking, smoking and partying hard while you are young. Then you will later become a decent adult because you’ve done everything you wanted to.”

Masato Imai/Momo Matsuura

Masato Imai/Momo MatsuuraHarajuku’s Lolita subculture emerged in the late 1990s in opposition to Gyaru, says Kawamura. “Lolita girls are hyper feminine and cute. They make an effort to look like a Victorian doll or princess and wear a dress with lots of ruffles and lace trimmings,” she explains. “They have their own dress code such as not making the skirt hem above the knees and exposing too much skin. They don’t smoke or drink. They go to tea parties, they usually don’t drink coffee.” She notes that some associate the Lolita style with the novel of the same name, but stresses this subculture has “nothing to do with a middle-aged man and a young girl.”

A sense of belonging

Subculture style is all about a sense of belonging, says Kawamura, with adherents bonded by sharing the same or similar fashion. “Many of the girls I have interviewed said ‘I have made so many new friends that I would have never met if I did not belong to this subculture.’ Their distinct fashion stands out, and sometimes it is ridiculed or looked down on but when they meet their fellow members, they know they are accepted as a member of the community.”

“There is a sense of camaraderie,” she adds. “Each district or a specific retailer in each district functions as a mecca for subcultural members. They can buy anything online, but making a trip to these places and buying at these stores give them a status and respect within the community.”

Shoichi Aoki/FRUiTS

Shoichi Aoki/FRUiTSDid the teenagers Aoki photographed seem to get a sense of belonging through membership of their particular tribe? “Yes, particularly for women it’s important, and when they become adults as well,” he says, adding the Harajuku styles have certainly influenced designer fashion, too, not just in Japan (he points to Yohji Yamamoto in particular) but internationally.

Kawamura has also noticed over several years of research, that genuine, die-hard dedication to subcultures is in demise, and many of these groups are either declining or no longer in existence. “Subcultures are usually marginal, hidden and underground. But once they are popularised and commercialised, they spread widely to the masses which goes against the basic subcultural values.”

Carl Court/Getty Images

Carl Court/Getty Images“Such a phenomenon could potentially alienate the authentic members. For instance, one may dress in Lolita only on weekends because she saw a celebrity wearing it. Some scholars say the term is outdated because no one is immersed into a subculture 24/7 these days. It is no longer a lifestyle as it used to be.”

She also echoes Aoki’s point that globalisation and digital progress have played their part, noting in particular the RuffleCon convention in Connecticut, which has grown in popularity in recent years, bringing together Lolita enthusiasts from all over the US.

“Somehow, Japanese Lolita is attracting Western girls,” she says. “Many of them have never been to Japan but found out about the subculture online.” In her latest book, Kawamura coined the term ‘upperground’ to describe a subculture that emerges from underground to become recognisable to the masses. “I treat it as something in-between underground and mainstream,” she says.

Joshua Lawrence

Joshua LawrenceWhat does the future hold, then, for Japanese street fashion? “My theory is the more distinct a style is, the more it binds followers together, and thus, it gives them a sense of community,” says Kawamura. “But if people do not feel the need to be part of a subculture, it begins to fade away. I think that today’s Japanese teens are well protected by their families that they don’t need to be part of anything or to make a social statement through fashion.” Aoki is more optimistic. “Boys’ fashion is becoming interesting lately,” he says. Maybe the FRUiTS archive will help inspire the next generation? “Yes, I plan to do something with the archive,” says the photographer. And besides, he adds: “I like change. And I believe in Japanese DNA.”

To comment on and see more stories from BBC Designed, you can follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. You can also see more stories from BBC Culture on Facebook and Twitter.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.