NED NASH

The following article first appeared in the American Orchid Society BULLETIN Vol. 52, No. 2, 1983 and is the first installment in a five-part series. It has been edited to conform to modern taxonomic nomenclature and availability of culture media and pesticides/insecticides. While now over 25 years old, the article still remains an excellent resource for the cattleya grower.

CONSIDER these two very common situations: 1) An inexperienced hobbyist, perhaps with no more than two or three orchid plants, visits a commercial nursery and selects a plant for purchase. The plant, in bud and giving promise of a lovely display, is not one our friend has ever read or heard about. Upon inquiring about its cultural needs, he is informed that it needs "Cattleya conditions but with a bit more light" ... or water ... or shade ... or whatever! Or, 2) A hobbyist of long experience decides that this weekend he simply has to repot some (or all) of his Cattleya collection. Perhaps he has procrastinated; perhaps he is over-anxious. In any case, most of his plants do well after potting, rooting and growing with vigor. One plant (usually his favorite), however, does not respond at all well. The plant manifests all the symptoms of dehydration, doesn't make any new growths or roots, and ultimately succumbs.

FIGURE 1. With sufficient light, a Cattleya should produce sturdy, upright new growths which require no staking.

The frequency with which these scenes occur across the country illustrates the fallacy of the old saw "everyone knows how to grow cattleyas." This is especially unfortunate as Cattleya culture is a universal foundation for general orchid culture. As most of us started serious orchid growing with a cattleya of some sort, we have a general knowledge of their cultural needs. Indeed, this knowledge becomes almost second nature quite rapidly.

It is simply because "How to Grow Cattleyas" is second-nature to so many that we encounter problems similar to those in our two situations. First, it is easy to forget that there are a lot of people who haven't the faintest idea what a cattleya even looks like, let alone how to grow one. Even those with a rough idea of how cattleyas should be grown are often hard-pressed to explain why they use a certain cultural practice. Second, even the most experienced grower may become complacent and make mistakes like our friend in the second situation. No orchid grower ever outgrows the need for observation. Properly observing a particular plant's growth habits and patterns can usually prevent problems like those described above.

The following articles are intended both for the beginner and the more experienced grower. While a relative newcomer to orchids, I have been very fortunate to learn from some of the most experienced men in orchids. Many of the illustrative anecdotes and observations in this series have been kindly passed on by Mr. Leo Holguin, General Manager of Armacost & Royston. Mr. Holguin has been growing with Armacost for nearly 50 years and his experience in Cattleya culture is undoubtedly second to none.

I should stress that, while aspects of culture will be discussed in separate sections, this is largely for convenience and ease of understanding. All cultural factors are equally vital to the successful growth of cattleyas. Additionally, no one factor can be separated from the others. All facets are interrelated and should co-exist in harmony.

LIGHT

Cattleyas require good light to grow and flower properly. Insufficient light is the main cause of their failure to bloom. If I am asked by a visitor to our nursery why their plant isn't blooming and if I determine that it has been at least one year since the plant last bloomed, I invariably have to answer with the preceding two truisms. Of course, there are important diagnostic questions to be asked. Is the foliage dark, glossy green? Do the growths grow straight without staking? If the answers are yes and no respectively, the plant has been grown with too little light. The foliage should be medium, olive green, and the growths should develop b and erect, as should the flower spikes.

Another more severe symptom of too little light occurs when the oldest bulbs die while the new vegetative growths get progressively smaller and weaker. This is analogous to the behavior of house plants grown with too little light. Because light is essential to the chemical reactions which produce a plant's energy, a plant receiving insufficient light will draw nourishment from older portions to subsist and to produce new growth. Since there is a net loss in any energy transfer, new growth will become increasingly weaker until the plant finally succumbs.

How do we know when our cattleyas are receiving enough light? The new growths should grow straight without staking (see FIGURE 1) and form nice, plump pseudobulbs. Seedlings should show progressively larger pseudobulbs until a mature size is reached. Inflorescences should emerge cleanly, growing straight with a minimum of staking. Foliage should be firm and a medium olive green. (Because most cattleyas are fertilized heavily today, owing to fir-bark culture, such plants tend to be greener than those grown in osmunda which require little or no fertilizer.) Light meters are a valuable tool but should not be relied on too heavily.

Optimum light conditions vary somewhat from region to region. In areas like Florida or Hawaii, cattleyas may be given nearly full sun, while in areas similar to ours in California, plants are best grown with 40-50% sunlight. This is a good example of why close observation of plant growth is a better indicator of proper light conditions than reliance on a light meter. Here at the nursery, we use a light meter to confirm our observations. With a little practice, one can walk into a greenhouse and "feel" if the light is right. Here again, I must emphasize the importance of keen observation of the conditions under which your plants are grown.

FIGURE 2. Heat build-up from too much light caused the yellow patches on these cattleya leaves.

Helpful, too, is an understanding of the preferred habitats of Cattleya species. The majority of horticulturally important species grow as epiphytes in the middle elevations of the subtropic. Epiphytism is generally thought to have evolved partially to enable the plants to obtain sufficient light in the often dimly lit forest by getting them up into the more brightly lit canopy. Most epiphytes, cattleyas included, do not grow where they will be exposed to full sun for long. Inner branches, or those under the uppermost canopy of foliage, are the preferred locations. In such areas, while the plant may be temporarily exposed to full sun, it receives bright, dappled light but remains protected from too much sun. If a plant is exposed to the full sun by loss of its foliar protection, its own foliage will burn, as would happen in your greenhouse.

FIGURE 3. Given time and continued over-exposure, "sunburned" tissue turns dark. These burns can greatly reduce a plant's ability to manufacture food.

I should point out that light itself does not cause the foliage to burn. It is the heat build-up caused by light which causes burning. This has several ramifications. For example, leaf heat build-up is probably the major limiting factor in windowsill or under-lights culture due to the difficulty of providing adequate light, under these conditions, without overheating the foliage. Even if the leaves do not actually show the symptoms of leaf burn (see FIGURES 2, 3), physiological processes may become so stressed that the plant(s) will grow poorly. Cattleyas, especially the smaller-growing types, can be grown under these circumstances but more care must be exercised than might be supposed. Heat build-up is also the reason your orchids "melted" on that hot day, even though you parked your car in the shade.

Plants grown in too much shade will burn even more rapidly than those grown with proper light. Remember your first day at the beach after a long winter? The fact that the dark green foliage will draw heat even more rapidly only exacerbates the problem.

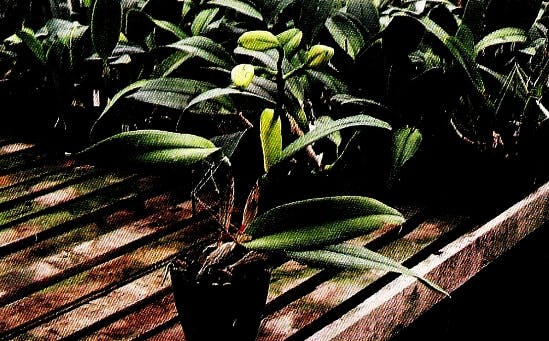

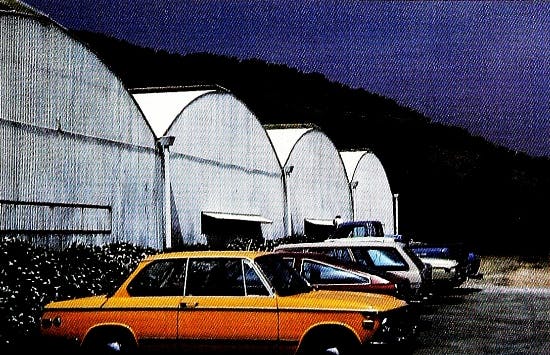

FIGURE 4. This greenhouse is properly shaded by lath on the side and a layer of shadecloth suspended on a frame above the roof. With shading, leaf-burn is unlikely.

If you use a paint-on shading compound on your greenhouse, it is imperative that dirt and dust be washed off (by a rain or with a hose) before the compound is applied. If the paint is applied over a dirty surface, it will quickly turn dark. Not only will the light quality be poor, but the dark color will draw heat into the house. Hot, shady conditions are a serious problem for cattleyas. Many growers make the mistake of laying shade-cloth or saran directly on the roof of their greenhouse, or placing it inside directly under the glass. While the light quality will be good, the dark shade cloth will draw heat into the greenhouse. Shade cloth should be suspended 8-18" above the glass on a frame (see FIGURE 4). This traps a layer of cooler air next to the glass, helping to keep temperatures down.

FIGURE 5. By feeling a leaf, the grower can determine whether the threat of light-damage exists under present conditions.

A good general test for heat buildup is to feel the leaves (see FIGURE 5). Ideally, they will feel cool to the touch. If the leaves are warm or hot, the temperature must be lowered however possible. A good temporary solution, the one we use as we have no artificial cooling, is to increase air circulation and spray the plants lightly overhead (see FIGURE 6). The evaporative effect will cool the foliage nicely.

It is clear that light and temperature are closely related. This brings us to a discussion of the proper temperature range for cattleyas.

TEMPERATURE

FIGURE 6. Spraying cattleyas with water is one way of lowering leaf temperature and reducing the risk of injury.

In nature, Cattleya species may be subjected to temperatures ranging from the low 40's to nearly 100F. However, conditions are generally more moderate, in the mid-50's to the upper-80's. Modern hybrid cattleyas are much modified by exceptions to the rule. Some knowledge of these exceptions and their part in any given hybrid is necessary.

For example, many standard, yellow Cattleya hybrids tend to resent lower temperatures owing to the presence of Cattleya dowiana in their background. Those who have experience in growing (or trying to grow) Cattleya dowiana are well aware of the finicky nature of this species. On the other hand, most of the smaller-growing, red Cattleya and related-hybrid color shades will enjoy slightly lower temperatures than standard hybrids. Indeed, these types attain their best color only when the plants can be grown cool and bright. This habit can be traced to the influence of species formerly classified as Sophronitis and Brailian Laelias. Most cattleyas can be grown in the same area for many, if not all growing environments have micro-climates that can be utilized to keep different types happy. For example, it is warmer near the heater and cooler away from it. Hybrids or species requiring more light can be hung higher in the greenhouse, while those preferring more shade can be protected by the foliage of other plants.

In general, cattleyas enjoy a temperature range of 55-60F night and 75-85F day under cultivation. The 15-25 degree differential between day and night is essential for proper growth and flowering. Unless a cattleya receives a cooler, dark "rest" at night it will quickly exhaust its food reserves. This accounts for the weak growths and burned leaf tips on plants that are artificially supplied with overlong day-lengths. Also, most cattleyas are photoperiod- as well as temperature-sensitive. The bloom season is determined not only by day length but by seasonal temperature variation. Experiments have shown that many cattleyas simply will not bloom if the temperature is maintained above 70F.

FIGURE 7. Enhanced air movement, provided here by perforated plastic tube attached to a high-speed fan, maintains even temperatures throughout the growing area while it cools the plants.

There are, of course, situations where it will be impractical, or indeed harmful, to maintain optimum temperatures. Many of the southeastern states may have periods during summer months where the night temperature doesn't drop below 70F. Because these periods are usually accompanied by very high humidity, evaporative coolers are ineffective. Air conditioning is impractical owing to energy costs. Fortunately, these periods are unusually not prolonged and most cattleyas will remain unaffected.

Conversely, the northern states will have periods during the winter when it is difficult to maintain a day temperature of 55-60F, let alone at night. Even if such a night temperature could be maintained, it would only serve to force the plants in a manner analogous to maintaining a constant HOT day and night. In this case, however, the result would be doubly harmful as the forced growth would develop under short-day, low-light conditions. Such growth would be very weak at best and very susceptible to rot and fungal problems. For this reason, experienced northern growers know they can allow their greenhouse to drop into the low 50's or mid-40's under such conditions, thus maintaining a day/night differential of 10-15F. It is advisable to be cautious with watering under these circumstances.

At this point, common sense must be stressed. While cattleyas require a temperature differential to do their best, do not go overboard. We have found, and the experiences of others have backed this up, that cattleyas function best when the temperature differential is not too great and when the temperatures are run at the lower end of the optimum. In other words, they will grow and flower at maximum potential at approximately 60F night (or a little lower) and 80F day. Flowers developed under such nice, even temperatures have the best size and substance because they have developed slowly and evenly. We have found this to be very noticeable at Armacost and Royston since our move to the Carpinteria Valley a little over eight years ago. We are approximately 90 miles north of Los Angeles and within one mile of the ocean. We find that the same Cattleya cultivar will have a flower much improved over how it appeared in the Los Angeles area. We feel this is entirely due to the very moderate, even temperature that we enjoy here so close to the coast. Common sense enters in deciding on the temperature range for your own area. For example, high day temperatures are unnecessary in the north where nights are normally cool year-round; and one needn't worry so much about high night temperatures when the days are normally quite warm. Intense fluctuations of temperature are what must be avoided.

There are many ways of providing supplemental heat for cattleyas. The tried and true method, probably still the best, is underbench heating by steam or hot water. Pipes, finned or otherwise, are run under the benches with steam or hot water supplied by a boiler. This system has several advantages. The heat naturally rises with great efficiency through the plants. This type of heating does not overly dry either the plants or the atmosphere as gas heat will. Perhaps the major advantage is the excellent root growth promoted by this method. Plants seem to establish easily, quickly and have a better-developed root system. (This principle is widely used in other parts of the nursery industry for the rooting of tip propagations.) The biggest drawback to this system is the high, initial cost of the boiler and piping. However better plant growth and lower, long-term maintenance costs greatly ameliorate this initial expense.

The more common method of heating today utilizes a space heater. Larger units force air through a heat exchanger, thereby heating the air and distributing it throughout the greenhouse. The heat exchanger may be heated by boiler-generated steam, although a gas flame is the most common method. Smaller space heaters generally rely on passive heat distribution. These smaller units are generally placed on the greenhouse floor. The heat rises and is fairly evenly distributed by natural convection and any fans present. The larger, fan-driven heaters are usually suspended from the greenhouse roof. Fanjets may or may not be used. Gas heat tends to be drying, although this is usually not a serious problem. The biggest drawback we have found with this type of heater is heat-exchanger failure. The welded seams rust out and the resultant leakage renders combustion of the gas incomplete. The non-combusted gas escapes into the greenhouse with its attendant problems of flower wilt and plant damage. We find that exchangers fail after 2-3 years and must be replaced. Thus the initially lower price may prove to be false economy.

With the rising cost of energy, many heat-conservation and solar heating schemes are being tried across the country. The A.O.S. BULLETIN has had several fine articles on these subjects in the last few years.

We like to grow our younger cattleyas, especially those right out of flask, a bit warmer and shadier than mature plants. This gives the fragile seedlings a better chance at survival. Young plants from flask are grown with 65-68F nights. As they are moved from flats into pots, they receive 62-65F nights. When potted just before flowering for the first time, they are moved into mature plant conditions. This method pushes the seedlings toward an earlier first-bloom. The advantage is that the plants are gradually hardened as they grow, rather than suffering through a transplant shock when quite young and more vulnerable. It also enables us to provide a b, hardened plant to our customers, easily adaptable to their conditions.

Important aspects of temperature control are proper ventilation and air movement. The admission of fresh, moving air to the growing area is beneficial for several reasons. Carbon dioxide is an essential ingredient to photosynthesis, and fresh air is the primary source. Moving air also helps to give an even temperature throughout the area and keeps leaf temperature down by evaporation.

FIGURE 8. Bottom and top vents on these greenhouses create a constant air exchange with the outdoors, keeping conditions fresh and fairly cool inside.

While fresh air and good circulation are obviously vital, do not go overboard. Provide just enough movement to eliminate stagnant conditions. This helps to keep down fungal problems. When our new greenhouses were constructed, we purposely had them built with a relatively high (twenty-foot) ridge. This increased volume helps to keep temperatures moderated and we need only open our ridge vents slightly to create a very nice air exchange. We have recently added bottom vents along the south face of our range. These are an excellent way of cooling a greenhouse. The cooler air enters at bench level and rises, as it warms, to exit through the ridge vents. By using these passive cooling methods, we very seldom need to use our fanjet blowers for cooling, except under very extreme conditions (FIGURES 7 and 8).

Naturally, high houses such as ours are impractical in cold climates, owing to the large, extra volume to heat. In colder areas, the smaller houses in use require more active air circulation, usually by turbulator-type fans (these draw air up toward the ceiling), and/or circulator fans that move air laterally. Many people have a tendency to get carried away with fans to the extent that they have near gale-force winds blowing through their houses. This is unnecessary and a point of diminishing returns can be reached. Plants can be stressed by excessive fans drying them too quickly.

With experience, you will readily "feel" when the greenhouse is right. The air should be a pleasure to breathe, a combination of good, earthy smells and full of oxygen. The house should feel light and buoyant, as a spring morning might. If you feel good in your greenhouse, so will your plants.

Thus far we have discussed the relationship between light and temperature and the roles they play in the growth of cattleyas. The next article will discuss the water and humidity requirements of cattleyas.