I wanted to be her.

I wanted to be Nan.

I knew her before I knew any of the others. William Eggleston, Richard Avedon, Diane Arbus, Helmut Newton—these names meant nothing to me, not yet. I was what adults called a moody teen, given to romance and melancholy, which I confused with melodrama. I would have liked to forget those versions of myself, to forget that hunger, that sorrow. I would have liked to forget the version of myself that bandied about words like “truth” and talked seriously about wanting to be real, to feel real. We lived in the heart of Santa Clara Valley, better known to outsiders as Silicon Valley. There were still, as late as my teenage years, cherry trees, and plums, prunes, almonds—vestiges of the Valley’s former life as “The Valley of the Heart’s Delight.” John Steinbeck could still write rapturously, in East of Eden, of the Valley’s wildflowers: “The spring flowers in a wet year were unbelievable. The whole valley floor, and the foothills too, would be carpeted with lupines and poppies. Once a woman told me that colored flowers would seem more bright if you added a few white flowers to give the colors definition. Every petal of blue lupine is edged with white, so that a field of lupines is more blue than you can imagine. And mixed with these were splashes of California poppies. These too are of a burning color—not orange, not gold, but if pure gold were liquid and could raise a cream, that golden cream might be like the color of poppies.”

The poppies and lupines were mostly gone, as were the cherries and the plums, but the same molten sun beat down on freeways and strip malls, on subdivisions and golf courses, and on acre upon acre of low-slung office parks. In the beige heart of Santa Clara Valley, I dreamed. I dreamed of a world more visceral and real than the one before me. As a child of visual culture, I entrusted my self fashioning to images. I fed my eye on Rolling Stone and Vogue, and whatever magazines I could find in libraries and bookstores. It was in this context that I found Nan Goldin.

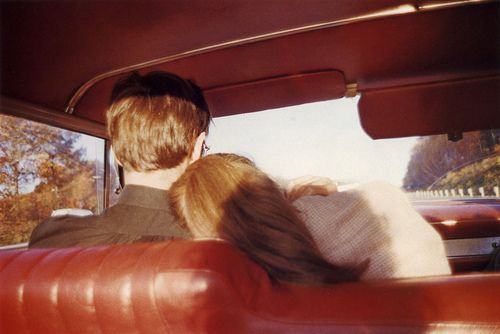

Her pictures pulled you in. They lingered as after-images, stills from some film too terrible to complete, too urgent to forget.

They had an ugliness that felt deeply intimate—retinal images transferred from eye to eye—but they were also full of a seedy glamour.

In those years, I was still hanging around San Francisco, going to clubs and concerts. Those bodies on stage — all heat and light—were feral and seductive. In the midst of sweetness, there was always something coiled back.

* * *

To say that I was interested in music is to miss the point. I wanted two things from music: ecstatic release from the ordinary, and glamorous charisma. Goldin’s photographs skirted the edge of those experiences. They brought me in contact with fragments of a different world, one I barely understood (or, more truthfully, did not, could not, understand at all). I didn’t need to understand that world. I just needed to know that it existed, out there. There would be a way out of suburban Santa Clara Valley.

I knew what Pete Seeger meant when he sang about the houses made of ticky-tacky. I saw them whenever we went into San Francisco. My own part of Santa Clara Valley was rather less picturesque. Until Google made its home in Mountain View, our claim to fame had largely rested on the presence of Shoreline Amphitheater, a stadium-sized performance venue (dare I say arena) whose bookings were exclusively handled by Bill Graham Presents.

We did not have pastel stucco houses on hills. What we did have were strip malls. And actual malls. Throughout most of my high school years, the landscape of leisure and the landscape of consumption were one. Even as a small child, I had already intuited this state of late capitalism. My favorite game, at age four, was going to the Metropolitan Museum and choosing what I wanted to buy.

There was a place on the Bay where I could sit and watch the burrowing owls play while eating an ice cream sandwich. The ice cream came sandwiched between two oatmeal cookies, and I liked the way the salt of the cookie cut against the sugar in the cream. The wrappers were printed with a stylized illustration of San Francisco’s Playland by the Sea, a Jazz Age amusement park that was long gone. The image was inked in a Sixties palette of avocado green and navy. I sat there with my ice cream, and I loathed the middle-class stability that permeated our world.

Later on, I would come to crave that same stability, especially in the years when the drought turned the hills to smoke, so that if I was in the right part of California I could watch the hills light up with orange-red thunderheads of fire. Black smoke billowed over the hills and it put me in mind of the fog rolling in over the Bay, only the fog was damp and clean and tasted of the tiny salt crystals that drifted with the wind.

* * *

I didn’t know that twist to the plot yet. At sixteen I would have said, let the fire come. Let it all burn away. Even pain is experience. And the hunger for experience—the desire to be something more than blank—obscures the fact that to be open and blank is both a privilege and, as some might say, a blessing. I searched for the point because it had not yet occurred to me that there may not be—there may never be—any point.

I looked to her photographs for something of that fire and smoke. The photographs carried their own atmosphere—salted, tropical, damp. Goldin’s colors bordered on fetid. Her reds were like no reds found in nature. They were the reds of old fashioned dime store hard candy the cherry that tasted of dye and chemicals, that curled up on your tongue, sugared and yet still acrid. The bitter memory of cough syrup was never far behind. Her colors evoked decay, disgust, in their artifice. They could be baldly, intentionally unnatural. I could not match them with the sun-washed colors of suburban California. They came from elsewhere.

* * *

The first time that I saw Nan Goldin’s photographs as prints, instead of reproductions, was at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. They came from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. (Goldin assembled this series of photographs between 1979 and 1986. It was first published as a monograph in 1986). At the time, I was beginning to take my own photographs. My father bought my first real camera, as a high-school graduation present. All silver plastic, with rounded, rubberized corners and the sort of molded ergonomic design that was popular in the late ‘90s, it took passable pictures. I hoped that by getting behind the camera, I could transform my own life, for what was a camera but a magic box?

I dragged my camera around Berkeley and the Bay. My pictures were ugly, but not ugly enough. I was already in college then, still interested in photography but already feeling alternately repulsed, bored, and exhausted by the emphasis, in my photography classes, on technique and perfection. I didn’t want to become a flawless mimic. But I didn’t know what it was, exactly, that I wanted. More and more I discovered that I wanted photography to be a personal language. Private. Compressed.

* * *

I recently ordered a copy of Ballad—a paperback reissue—and was struck by how little I remembered of her statement, describing the photographs as performing the work of memory, as a supplement or substitute. Goldin wrote: “When I was eighteen, I started to photograph. I became social and started drinking and wanted to remember the details of what had happened. For years, I thought I was obsessed with the record-keeping of my day-to-day life. But recently, I’ve realized my motivation has deeper roots: I don’t really remember my sister. In the process of leaving my family, in recreating myself, I lost the real memory of my sister. I remember my version of her, of the things she said, of the things she meant to me. But I don’t remember the tangible sense of who she was, her presence, what her eyes looked like. What her voice sounded like. I don’t ever want to be susceptible to anyone else’s version of my history. I don’t ever want to lose the real memory of anyone again.”

* * *

For a long time I didn’t go back to Goldin’s photographs. I was working on my own poetry —shearing away affect — to create a language of compression. In my own melodramatic way (contra the minimalism that I wanted to inhabit), I saw my task as a clearing — taking a razor and cutting away everything extraneous. Goldin’s aesthetic —committed to a certain kind of presence and beholding — reveled in excess and affect. We were always on the verge of Victorian sentimentality, or Southern Gothic. There was something about this aesthetic that felt undisciplined. I levied at Goldin’s photography the same critiques that critics once leveled at Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton.

When I was backing away from this display of the personal —this excess of emotion and sentiment— it never occurred to me that I was also paring away the self.

* * *

I didn’t see the slideshow version of Ballad until 2016, when the MoMA put its copy on exhibit. By then I was in my thirties and had a different relationship to art and photography, to the very act—and idea—of looking.

I saw it for the first time on a weekday morning, with tourists and other people who were—voluntarily or not—at leisure. To get to the slideshow, I had to walk past a small gallery of prints and ephemera. There were the hand-drawn posters, now elegantly framed. There was the famous photograph of Goldin with her black eye. There was the velvet curtain, and behind it—the projection room.

During a particularly troubled time, someone suggested I put my iPhone to work and keep a visual diary. In those years I referred to my phone as my prosthetic mind. What I saw—the strange, the beautiful, the repulsive, the mundane—went straight into that camera. And then I jettisoned those images from my own memory, so much so that later, going through albums, I am surprised by who I was, what I saw. The experience is something like standing in the surf, and suddenly feeling the undertow.

The slideshow version of Ballad is something like that.

If only I could just remember, prompts nostalgia. So there was the peach silk prom dress, and there was the restaurant we liked—And suddenly we are keeping company with ghosts.