(Graphic: iStock, Getty)

WASHINGTON — If the past couple of years have been about planting the seeds of change for both national security space operations and governance of space activities writ large, 2023 has been all about the struggle to keep the new shoots alive. And, as with any annual garden, the results has been mixed.

[This article is one of many in a series in which Breaking Defense reporters look back on the most significant (and entertaining) news stories of 2023 and look forward to what 2024 may hold.]

At the Defense Department, the Space Force has made some visible progress toward shifting the military space architecture toward a more resilient configuration based on larger numbers of lower cost satellites, and multiple layers of capability.

But despite concerted efforts by Air Force space acquisition czar Frank Calvelli, space acquisition reform at the macro-level has proven more vexing. In particular, fixing long-broken but critical ground system and software upgrade programs appears to be a Sisyphean endeavor — perhaps only resolvable with intervention from on high.

On the space governance front, the situation can best be described as “two steps forward, one step back.” This is certainly true for the Biden administration’s efforts to sort out how to manage the commercial space boom that DoD hopes to slipstream — although at the international level it might be the other way around due to the troubled geopolitical waters.

‘Pivoting,’ Slowly, Toward A Resilient Space Posture

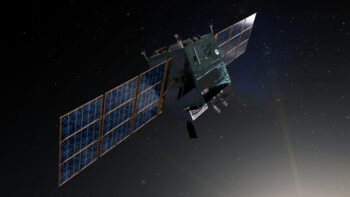

In January 2022, the Space Force’s first chief, Gen. Jay Raymond, promised to begin what he called a “pivot” to a new on-orbit posture that would be better shaped to withstand adversary attacks — moving from reliance on small numbers of exquisite satellites with bespoke ground systems to multiple interlinked and overlapping constellations of smaller, cheaper, more rapidly replaceable ones.

That pivot has been nothing like a ballet dancer’s pirouette, and more like the slowwwww turning of an aircraft carrier. But that said, this year, the service made a little headway.

Specifically, the Space Development Agency (SDA) has launched the first experimental data relay and missile warning/tracking satellites for its planned Proliferated Warfighter Space Architecture (PWSA), designed to make it harder for adversaries to negate US space capabilities via the sheer number of satellites available to US commanders. However, the agency has a long way to go to get to its end goal of some 1,200 satellites, new ground systems and a integrated battle management and control capability.

In addition, Space Systems Command (SSC) cleared Boeing’s Millennium Space Systems to begin production of the first six satellites for its planned Missile Track Custody constellation in medium Earth orbit, the company announced Nov. 27. Aimed at keeping tabs on hypersonic missiles, the constellation is expected to include as many as 27 satellites, with launches of increasingly capable variants on a two-year cycle starting from 2026 and running through 2030.

Space Acquisition Reform: Stoney Ground

With regard to expanding its use of commercial satellites and services for various missions, however, the Space Force has yet to make much headway beyond setting the table for future action with its new Commercial Space Office. First to be finalized in September, the service’s new space acquisition strategy was sent back to the drawing board by Chief of Space Operations Gen. Chance Saltzman with an eye toward getting it wrapped up by the end of 2023. That, several sources told Breaking Defense, isn’t going to happen.

Instead, service officials now expect it to be completed by early February 2024. Meanwhile, an overarching strategy on integrating commercial space capabilities into Pentagon efforts, being drafted by DoD’s space policy shop headed by John Plumb under the oversight of DoD Deputy Secretary Kathleen Hicks, also has yet to emerge.

At the same time, Calvelli is hoeing stony ground in his efforts to create a smooth path for ground systems and software updates long mired in repetitive cycles of missed milestones, cost overruns and program reorganization. While he’s put into place improved management practices that have won kudos from experts, a number of programs remain troubled.

For example, the Space Force’s once-touted Enterprise Ground Services effort to streamline and standardize how the myriad disparate ground systems (traditionally bespoke for each different constellation) essentially has collapsed. The service now reconsidering how to revamp its approach.

Calvelli’s high hopes to have the long-troubled Next-Generation Operational Control System (OCX) for the Space Force’s newest Global Positioning System satellites finally up and running by the end of the year also have been dashed. OCX, which is needed to operate the GPS III birds and to control use of the military-only, jam-resistance M-code, has been delayed yet again. An Air Force spokesperson told Breaking Defense acceptance of the developmental system from prime contractor RTX (formerly Raytheon) is now expected in June 2024 — a six-month delay that nonetheless “is still within the threshold baseline date approved by the Defense Acquisition Executive.”

That said, the spokesperson also noted that OCS isn’t expected to be “Ready to Transition to Operations,” (i.e.; actually usable) until February 2025. OCX was originally supposed to become operational in the 2011-2012 timeframe.

Likewise, the ATLAS, the Advanced Tracking and Launch Analysis System, being developed by L3Harris to replace the 1980’s-era Space Defense Operations Center (SPADOC) computer system and software, also has been delayed until August 2024.

Space Governance: Choppy Waters

The White House’s long-awaited draft bill to assign regulatory authority for new types of space activities — including missions such as on-orbit refueling that the Space Force is eyeing to underpin its push for space mobility — was released Nov. 15. But its plan to split that authority between the Commerce and Transportation Departments caused a lot of churn within industry and on Capital Hill, where sentiments tend to lean laissez-faire on all things regulatory.

As 2023 winds to a close, department officials and National Space Council staff are campaigning to convert skeptical interlocutors in hopes of steering the years-long debate toward the administration’s port.

At the United Nation’s dual headquarters in Geneva and New York, the State Department-led efforts throughout 2023 to craft new norms for responsible behavior in space picked up momentum — for example, 37 countries have signed up to the US proposal for a testing moratorium on destructive anti-satellite (ASAT) missiles — only to be dashed by Russia, in part as a response to Western opposition to Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

Russian diplomats wielded UN procedure and Moscow’s veto power to torch the results of the UN Open Ended Working Group (OEWG) on Reducing Space Threats Through Norms, Rules and Principles of Responsible Behavior that began in February 2022 and ran through this September.

In October, the choppy geopolitical waters led to a split in another set of ongoing UN talks on norms into two separate procedures: one spearheaded by the United Kingdom with support from the US and its allies; the other headed by Russia and China.

All in all, 2023 has been a slog for the national security space community — including this exhausted chronicler. And hang on to your hats, readers. Given that it is a presidential election year here in the US, we may all find ourselves looking back to 2023 somewhat fondly as the calm before the storm.