And all will be well

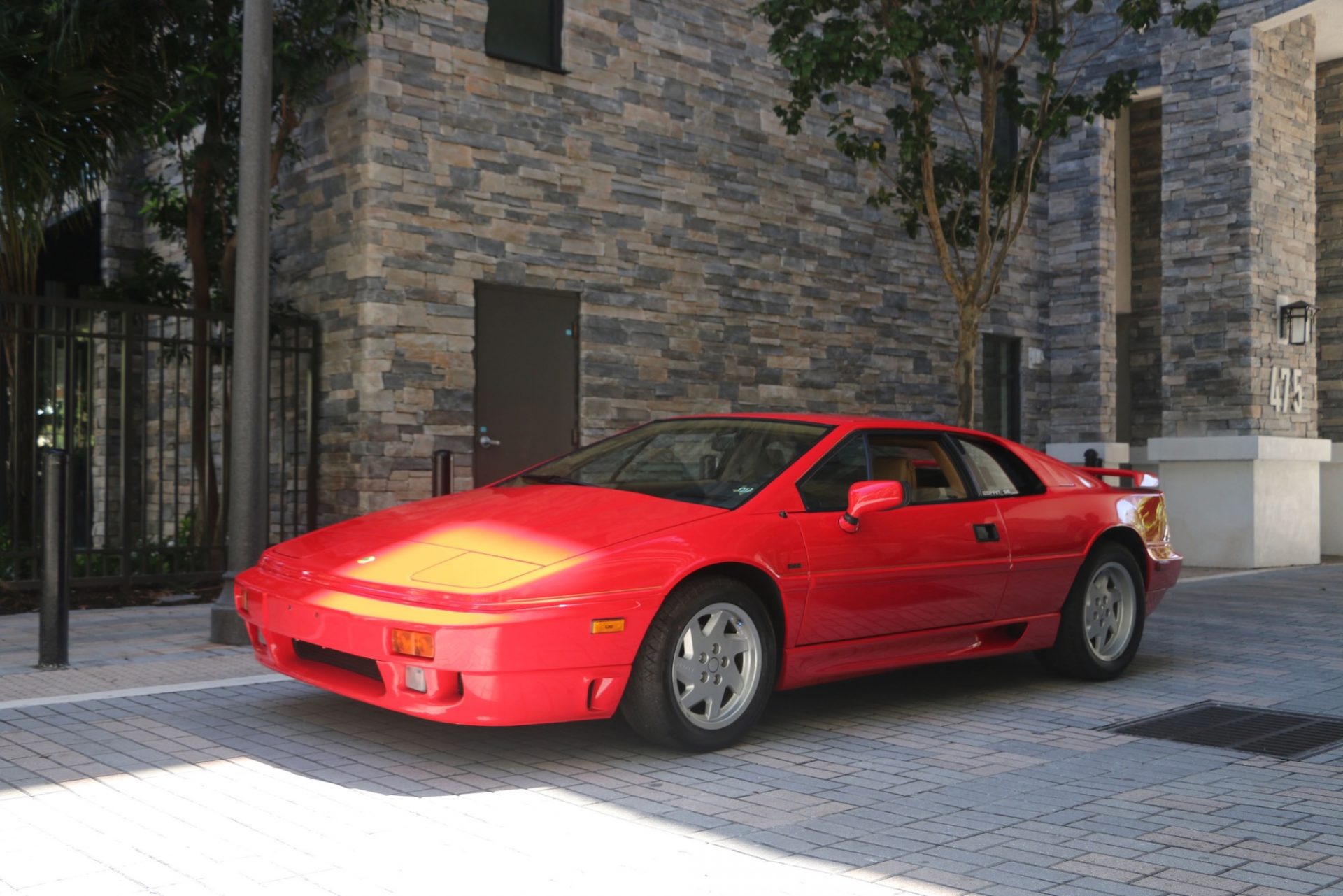

In its long history, the Lotus Esprit is the perfect expression of engineering, ingenuity, constant development and driving pleasure.

Colin Chapman saw how it went at Ferrari: On the racetracks of this world, the Italians took victories and fame. This also radiated off the road cars that could be built in Maranello and sold to customers for an absurd price. This earned Ferrari the money to build better racing cars, and so the game always circled nicely around itself. Although Chapman – who brought sponsorship to Formula 1 – could afford racing, and probably even earned money with it, Ferrari’s business model was of course much more exciting. And more glorious. He wanted something like that, too.

But one thing was also clear to Chapman: to reach the heights of Ferrari (and Porsche, too), he had to say goodbye to his low-priced kit cars as well as his low-volume products. He had to do everything differently than before, also everything differently than his previous competitors like Marcos or TVR – and everything better than Aston Martin, where they were only in the red despite their good name. The year was 1970, when Chapman and his engineers, above all Tony Rudd, had put together the key data for two completely new Lotus, the projects were called M50 (from which the new Elite, Type 75, later Type 83) and M70. The heart and soul was clearly in the M70, with which Chapman wanted to reach the higher spheres.

Now things are getting complicated for the first time. Opinions differ as to whether it was designer Oliver Winterbottom who brought Colin Chapman and Giorgetto Giugiaro together at the 1971 Geneva Salon or whether Giugiaro approached Chapman directly. What is certain is that Chapman could well have imagined that Giugiaro/Italdesign would take over the design for the M70 – those were the years when car manufacturers could still boast about the Italian design studios. Besides, Turin had the right experience in building show cars and prototypes, so they soon sent a modified chassis of a Lotus Europa together with some employees to the south. Whether Chapman also knew in 1971 that Giugiaro was already working on the Maserati Boomerang is again uncertain. He must have noticed it at the 1972 Geneva Salon at the latest, because both vehicles were on display at the Italdesign stand, i.e. the M70 (known as “the silver car”) and the Boomerang. All similarities were, of course, absolutely coincidental.

So I guess you have to look back into the past a bit. In the late 1960s, the Italian Marcello Gandini was able to establish a new design language in automobile design with the concept cars Lamborghini Marzal (1967), Alfa Romeo Carabo (1968) and above all the Lancia Stratos Zero, which was then transferred to series production for the first time in the Lamborghini Countach (1971): the wedge shape. This also made sense for sports cars; a high rear with a tear-off edge functioned like a spoiler – and provided sufficient downforce for the increasingly powerful and faster vehicles. These early wedge shapes were used exclusively on mid-engined sports cars. Giorgetto Giugiaro was also one of the designers who experimented with the wedge shape early on; his first “own” concept car, the Bizzarrini Manta in 1968, was clearly shaped in this way, and the Maserati Ghibli (1966) may probably already be counted among them.

Whatever the case, Chapman was happy with Giugiaro’s design, even if he had certain concerns about how the wedge shape would affect handling at higher speeds. But it was with the acceptance of the project that the problems really began. Giugiaro had made the shape of the M70 in an aluminium alloy, which was out of the question for Lotus: it had to be fibreglass. Which could be bolted to the steel frame chassis with central support. First a 1:4 scale model was built, which could be tested in the MIRA wind tunnel. This led to some adjustments to the design, which were immediately implemented in the first prototypes (“the red car”, also known by its registration number IDGG 01), such as a less inclined and smaller windscreen.

An engine for the new car had actually been available since 1970. Chapman had already done the groundwork in the mid-1960s when he specified the key data for his own Lotus engine: 2 litres displacement, four cylinders, four valves per cylinder, approx. 150 hp in the road version; he also wanted to develop a 4-litre V8 from this. But the resources were lacking. Steve Sanville and Ron Burr were able to develop a cylinder head, but there was no suitable block. An own development was (Chapman) too expensive, but when Vauxhall introduced its new 2-litre engine in 1967, the Lotus engineers quickly realised that this could be an optimal starting point. Chapman was able to secure ten blocks and four engines, so they could start building their own engines.

Once again, one of Colin Chapman’s “strokes of genius” followed: even before the power unit with the designation 907 had been completely developed, he had sold 15,000 examples to the Norwegian-American businessman Kjell Qvale, who wanted to install these engines in his “Jensen-Healey” project. This vehicle came onto the market practically without testing – and was a disaster. The cylinder liners warped, the oil consumption was exorbitant, the Lotus engines died miserably in rows. This was the death knell for the Jensen-Healey, but Chapman had used it to finance the development of his engine – and was able to correct the worst mistakes before launching his own model with the 907.

What Lotus also lacked was a gearbox. How the English came to look for one at Citroën/Maserati is not known. But the gearbox that had been developed for the Citroën SM and was later used in the Maserati Merak proved to be a good choice. It did need some design adjustments, a new clutch bell as well as a new construction with rods and cables for the gear lever, but the English succeeded impeccably, there was nothing wrong with the Citroën C35 gearbox in the Lotus.

There were, after all, a few more “foreign parts” on the new Lotus. The front suspension came from the Vauxhall Cavalier Mk 1 and consisted of upper and lower wishbones with coil springs and telescopic shock absorbers as well as a stabiliser. The front disc brakes were also from the Vauxhall Cavalier; the rear disc brakes were inboard. The rear suspension was a different story anyway. It consisted of trailing arms tapering inwards with lower wishbones. The driveshafts had to provide the transmission of the suspension forces into the engine and transaxle assemblies, which meant that the car was highly dependent on the stability of these suspensions. The rack-and-pinion steering was not servo-assisted. The fibreglass body was formed from an upper and lower section which were glued together.

The company founder had demanded of his team that the new model be ready for Christmas 1974. The boys didn’t manage that, but in January Tony Rudd picked up his boss in IDGG 01 at Heathrow Airport. Together they drove to Hethel – and only broke down. Chapman decided it was time to present the Esprit to the world, first in Paris, then in London. Previous Lotus disciples were shocked: the end of the low-priced kit car sports car was nigh. But a clearly wider audience was excited, Giugiaro design, a decent engine (160 hp at 6580 rpm, max torque 190 Nm at 4800 rpm) – Lotus seemed to be on its way to a glorious future. Even though the first series of the Esprit (from 1976) never managed the performance figures given by the factory: 6.8 seconds was the hope, the reality was probably over 8 seconds. The top speed of 222 km/h was probably more of a marketing gag, but the first Esprit did manage over 200 km/h. But at least the new Esprit weighed only 900 kilos.

Talking of marketing: when the head of public relations at Lotus, Don McLaughlan, heard that a new James Bond film was to be released in 1976 with the title “The Spy Who Loved Me”, he had all the lettering on a new Esprit masked off and parked it outside Eon’s offices at Pinewood Studios outside London as late as 1975. As soon as the production team saw the Lotus, he had it driven away – and followed by the James Bond crew. The producers were so impressed by this performance that they asked for two vehicles, in other words: virtually begged. And then a third, whose body could be mounted on a submarine. Lotus didn’t pay a single pound for one of the most grandiose car performances in film history. And the publicity was far grander than the cars of the first series.

As early as 1978, the Esprit S2 was a problem solver first and foremost. The interior of the car was significantly upgraded from the cheap and rather shabby standard of the Series 1, the seats were significantly widened, the previously hard to see Veglia instrument panel was replaced by redesigned Smiths gauges, illuminated switches and other fittings from the Morris Marina were fitted. Intake and cooling ducts were added behind the rear side windows, and the tail lights were converted to units from the Rover SD1. The front spoiler was redesigned by Giugiaro to create a more effective vacuum under the car. While the first series of the Esprit was still equipped with (cheap-looking) rims by Wolfrace, the S2 received noble special rims by the Italian company Speedline.

Work was also carried out on the engine, which was called the 912 with a displacement of 2.2 litres. The maximum power remained the same, but the maximum torque was increased to 217 Nm. Only just 88 units of the 2.2-litre Esprit were built, some of them in a John Player Special livery, making them the rarest and consequently most sought-after Esprits ever. But Chapman knew that the 912 was only a stopgap, that either a bigger engine was needed – or then a turbo.

This came in 1980, numbered backwards as the 910. This power unit was a tour de force: Garrett-AiResearch T3 turbocharger (charged at 0.55 bar), dry sump lubrication, new camshafts, sodium-filled exhaust valves, There was also a reinforced clutch and improved engine mounts. The improvements were not limited to the engine, however; the chassis was also completely redesigned and given 50% more torsional rigidity. The front suspension from the Vauxhall was replaced by a proprietary design consisting of an upper wishbone in combination with a lower wishbone. The weak point of the rear suspension, where the driveshafts had to provide stability, was eliminated, and the new chassis design included upper wishbones that took over this task and provided much better support, while at the same time relieving the load on the driveshafts. This engine was first fitted to the Esprit known as the “Essex”, painted red/blue in the colours of Lotus’ main Formula One sponsor at the time.

Giugiaro was commissioned to design a body kit for the car which included a deeper wrap-around front spoiler, side skirts with integrated rear air ducts, a rear spoiler lip, a tailgate with air vents and more prominent bumpers. Added to this were 15-inch alloy wheels from Compomotive with wider 60mm tyres. And in the headliner of the deep red leather interior were the control components of an all-new Panasonic stereo system. The “Essex” not only looked good, outside and inside, it also delivered: 210 hp at 6250 rpm, 271 Nm maximum torque at 4500 rpm, 0 to 100 km/h in 6.1 seconds, 241 km/h top speed.

As early as 1981, the third series of the Esprit came onto the market, offering slightly more headroom and a larger footwell. The range remained the same, the S3 was available with the 160 hp 2.2-litre engine (912) or with the 210 hp turbo (910), although the dry sump lubrication was replaced by a classic wet sump. More importantly, the S3’s build quality was significantly better than that of its predecessors – Colin Chapman was well on his way to making Lotus a serious sports car brand. Only: Chapman once again lost himself in peculiar projects, this time it was DeLorean. The American sports car that was supposed to be built for eternity ended in scandals and a steep bankruptcy. And Chapman died unexpectedly on 16 December 1982.

The charismatic, ingenious company founder left behind chaos, a huge mountain of debt – and above all a big gap. Although the Esprit continued to be produced, and from 1985 onwards there was also a so-called “High Compression” version (for the type 912: compression 10.9:1, Nikasil-coated aluminium cylinder liners, 180 hp at 6500 rpm – for the type 910: compression 8.0:1, Mahle pistons, boost pressure 0.65 bar, 215 hp; from 1986 onwards with Bosch-KE-Jetronic), it was clear in Hethel that the Esprit could not go on like this. And they already had a new arrow in their quiver with the “Etna” project. The only thing missing was money.

Then came General Motors, in 1986, and Peter Stevens, who later became famous for the design of the McLaren F1, who subtly and at the same time magnificently modernised the ageing Esprit. Actually, the new car should have been called Series 4, but the changes were so profound that it was called X180. For the production of the body, Lotus patented a system called VARI (Vacuum Assisted Resin Injection). In this process, a vacuum is used to assist the flow of resin into the specified mould. Lotus used VARI to inject Kevlar into the roof and sides of the body to significantly improve rollover protection. This had the added benefit of making the body 22% stiffer overall.

With the X180 came many innovations over time. The Citroën C35 gearbox was replaced by the gearbox from the Renault 25. As a result, the disc brakes, which had previously been on the inside, had to be moved to the outside. From 1989 there was a new MPFI petrol injection system (Multi Point Fuel Injection) from Lotus/Delco. This then also required the so-called “charge cooler”, an air-water-air turbocharger intercooler. This new engine version was designated the 910S, produced a whopping 268 hp (and even 280 hp with overboost), catapulted the Esprit to 100 km/h in 4.7 seconds and a maximum of 257 km/h. There was also a cheaper version with 228 hp – and an Italian variant with only 2 litres of displacement and then 240 hp. But that was not all: there were also twenty Lotus Esprit Turbo X180R. These cars were based on the Type 105 racing cars and were fitted with a high-performance Type 910S engine, which had larger injectors and a revised engine management system, increasing power to 286 hp. And finally, there was the Lotus Esprit Sport 300, which had a Garrett T4 turbocharger with an improved intercooler and larger inlet valves, as well as the necessary changes to the engine management system. This gave the machine a whopping 306 hp at 6400 rpm and a maximum torque of 390 Nm at 4400 rpm.

But there was more, this in the Series 4 built from 1993 onwards. There was re-styling again, this time by Julian Thomson (who was later responsible for design at Jaguar/Land Rover). Under the bonnet, everything remained the same as in the X180 at the beginning, finally power steering, a few more horsepower, still an Italian 2-litre variant (designated GT3, the engine wore the number 920). But the big thing was truly big from 1996 onwards: the V8 finally arrived in the S4. This new engine was based on the well-known 900 series, so it also had four valves per cylinder, was additionally ventilated by two Garrett-AiResearch-T25/60 turbochargers (without intercooler). The Type 918 had a displacement of 3.5 litres and 350 hp, which in the imaginatively christened Esprit V8 made it over 280 km/h and took it to 100 km/h in 4.5 seconds. The Renault gearbox was strengthened with a more massive input shaft.

In 1999, the Lotus Esprit Sport 350 was added, which was easily recognisable by its huge rear spoiler; only the connoisseurs saw the AP racing brakes. It is not quite clear how many examples of this last model variant, which was given a further facelift in 2002, were built – but it can be assumed that probably 10,675 Lotus Esprits were built between 1976 and February 2004. Only the wonderful Elise was to replace the Esprit as the most successful Lotus of all time. And it is only today that we are beginning to realise what an excellent car the Esprit actually was; prices are soaring.

We have more exciting vehicles in our archives, including some Lotus.

Be First to Comment